|

|

|

|

The Encino Vista Project - Already Completed?

|

|

|

Encino Vista Project area by Forest Road 76L. Prescribed fire applied in 2014 — Photo: The Forest Advocate

|

|

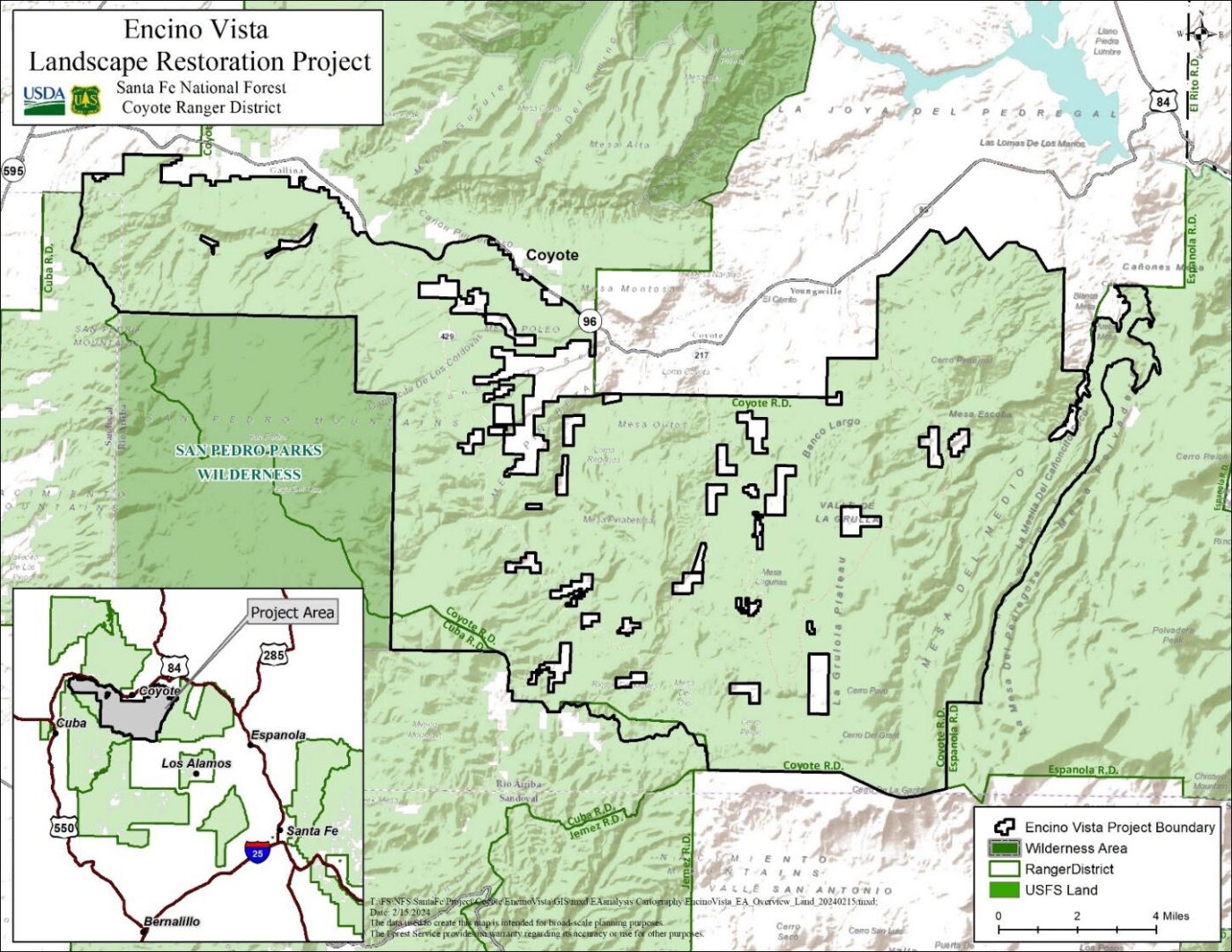

Recently, I went on a tour of the northwest section of the Forest Service’s proposed 130,305 acre Encino Vista Landscape Restoration Project area in the Jemez Mountains of the Santa Fe National Forest, about 15 miles northwest of Los Alamos. Like others who have seen the project landscape, my primary impression was that the “job” is largely already done.

|

Much of the landscape has already been logged and/or “thinned,” and many prescribed burns have been implemented. There are a few thickets and dense north slopes, but mostly the forested areas have been already opened up by tree cutting. There are both large and small openings in the tree cover, as the Encina Vista Project Preliminary Environmental Assessment indicates should be created by cutting and burning treatments. There are large meadows, or pastures, where cows often graze.

|

I have heard people say that in the past that the Jemez Mountains had some of the most beautiful forested landscapes in the West. I could see how that may have been true before logging, aggressive thinning, overly-frequent prescribed burns, overgrazing, and the construction of too many forest roads had occurred. The area we toured now looks degraded from the various human-caused impacts.

|

The grasses and understory are generally cropped down by the cattle, and there seems to be some soil damage, but still many areas could recover if the landscapes were left relatively free of human-caused impacts. Some previously treated areas are developing uncharacteristic vegetation, which doesn’t seem to easily return to more characteristic understory. In some treated areas the trees seem to be lacking in vitality, or even dying.

|

Aggressive treatments are likely to greatly increase the overall degradation of the project area and to excessively open the forest canopy, causing soils to dry out and much more uncharacteristic understory to develop. Endangered and sensitive wildlife species will likely be adversely impacted.

|

Much of the Jemez Mountains has already been heavily burned by recent wildfires, but the Encino Vista area has for the most part not been recently burned by wildfire. Past major wildfires in the Jemez Mountains include the 43,000+ acre Cerro Grande Fire in 2000, caused by an escaped prescribed burn set by the National Park Service. There was also the 2011 Las Conchas Fire that burned 156.000+ acres, caused by a spark from a downed power line during high winds. And there was the recent 45,000+ acre Cerro Pelado Fire, ignited in 2022 by an escaped Forest Service prescribed burn. This occurred at almost the same time as the 341,000+ acre Hermits Peak and Calf Canyon Fires on the east side of the Santa Fe National Forest, also both ignited by escaped prescribed burns.

|

Fire on Southwestern landscapes is a natural occurrence and can be ecologically beneficial and promote biodiversity, but in the Santa Fe National Forest in recent years there has been too much fire. The vast majority of the wildfire has been ignited by US Forest Service escaped prescribed burns. In the warming climate, we don’t know what will regenerate and what will not. Some areas do not appear to have much conifer regeneration and are possibly converting to shrubland, while other areas do have fairly strong conifer regeneration, even if there may ultimately be less conifer abundance.

|

Prescribed burn implementation safety is not necessarily improving substantially. Last week, despite a spring wind pattern, the Forest Service implemented a prescribed burn in the Carson National Forest, about twenty miles north of the Encino Vista project area – the Montoya prescribed burn near Canjilon. This prescribed burn was conducted in a scenario much like the Hermits Peak/Calf Canyon Fire – a spring burn implemented during a wind pattern, and red flag warnings issued for nearby areas a few days after the burn was ignited. The burn was ignited long before the monsoon season has arrived – so if the fire escapes, there will be little to stop it until the monsoons come. Fortunately, so far this prescribed burn has not escaped.

|

With some urging, the Forest Service has posted the Encino Vista Project preliminary environmental assessment comments on their website. 89 comments were submitted, which was a large increase from the 14 comments posted during the scoping comment period. The relatively small amount of public engagement for the largest cutting/burning project ever proposed in the Santa Fe National Forest was primarily due to the lack of sufficient public notice by the Forest Service. This is a major issue to residents of local communities, especially of the land grant community of Cañones, which will be very impacted by the project. This time, however, the Cañones community got together to write and submit comments, and many used The Forest Advocate comment guide. Also Forest Advocate readers submitted comments. Thanks so much to those who engaged – it takes dedication and not giving up in order to improve the situation in our forests.

|

The Forest Advocate submitted comprehensive comments along with WildEarth Guardians and the Santa Fe Forest Coalition.

|

Out of the 89 preliminary environmental assessment comments, only 8 are in clear support of the project. There are several others that supported some aspects of the project as proposed, but not other aspects. The remaining comments, which are the vast majority, are in opposition to the current project proposal, and many are vehemently opposed. Most commenters urged the Forest Service to complete an Environmental Impact Statement for the project. Some objected to how poorly the environmental assessment is written, and how it lacks substantive analysis and data. Many expressed concerns about the possibility of wildfires ignited by escaped prescribed burns, and the lack of sufficient egress for local residents to escape from such fires. And many expressed concerns about the potential ecological damage from aggressive cutting and burning treatments, based on damages from past treatments.

|

The Abbot from the local Cañones monastery wrote in his comments, referring to a meeting that the local residents had recently hosted in order to try to engage with the Forest Service:

|

|

|

I have lived in Cañones for only fourteen years, and do not have deep-seated roots here. I am a gringo, and know how gringos think, and what the USDA Forest Service [has is] a gringo mode of thinking. It runs like this: the forest is an object, we possess this object, and we are free to manipulate and control this object as we please. This was evident in the presentations made last night from members of the USFS. This is contrasted with how the locals think: the land is a gift given to us, our ancestors were good stewards of the land and we received this inheritance, our livelihood is from the land, and we do not separate it from ourselves. This first way of thinking looks at the forest as a problem to be solved. The second way of thinking cultivates reverence for the land, and an intuitive sense that we must work with the land rather than manipulate it.

So communication will always be failing, since the Forest Service thinks about the forest with their heads—sitting behind desks and crunching numbers about how to solve a problem. The local community thinks of the land with their heart, with their hands in the soil, possessing a religious attitude toward the forest, knowing that it has provided for their forbearers for centuries before a time that this land was not part of the United States of America. The land speaks a timeless wisdom, and the heart intuitively knows that the proposed plan is shortsighted.

In New Mexico, there is a strong feeling of ‘tierra sagrada’; that we live on holy land...and for outsiders to come in and show irreverence toward what is sacred to the local community is a sad story which has long been told in the Americas... The lack of reverence that has been shown to the earth for the past couple centuries has resulted in an ecological catastrophe of which we have dug a hole too deep to climb out. Let us stop this destructive trend now, and listen to the earth.

|

|

Yes, let's do all that we can to stop this destructive trend now, and to listen to the earth. That means developing strategies that work with natural forest processes as they adapt to current climate conditions, and to not try to impose a construct that is created primarily from the human mind with all its limitations, and is overly-based on estimations of past conditions. We need to stop believing we can save our forests from natural, and often beneficial, processes such as wildfire by redesigning ecosystems. For the most part, it doesn’t work. It’s time to move forward across the West with a new paradigm that preserves what is so precious in our forests – moisture, clean waterways, productive soils, diverse and abundant understories, and healthy trees.

|

The Encino Vista Project draft decision is planned to be released July 1, and then the objection period will commence. Also, the Forest Service’s analysis of the escaped prescribed burn which ignited the Calf Canyon Fire is due to be released within the next several weeks, over two years after the fire was ignited. The Forest Advocate will provide a synopsis and evaluation of the Calf Canyon Fire analysis in a future forest update.

|

|

|

|

Area masticated in 2012 and now proposed to be cut, pile burned, and broadcast burned, by Forest Roads 62 and 62B — Photo: Public Journal

|

|

|

“Ojo” unit proposed to be commercially logged. followed by pile burning, east of Forest Road103 by Forest Road 318 — Photo: Public Journal

|

|

|

Encino Vista Project Map — US Forest Service

Note the size of the project in the insert on the bottom left-hand corner

|

|

|

|

|